Taylor–Proudman theorem

In fluid mechanics, the Taylor–Proudman theorem[1] (after G. I. Taylor[2] and Joseph Proudman[3]) states that when a solid body is moved slowly within a fluid that is steadily rotated with a high  , the fluid velocity will be uniform along any line parallel to the axis of rotation.

, the fluid velocity will be uniform along any line parallel to the axis of rotation.  must be large compared to the movement of the solid body in order to make the coriolis force large compared to the acceleration terms.

must be large compared to the movement of the solid body in order to make the coriolis force large compared to the acceleration terms.

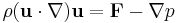

That this is so may be seen by considering the Navier–Stokes equations for steady flow, with zero viscosity and a body force corresponding to the Coriolis force, which are:

where  is the fluid velocity,

is the fluid velocity,  is the fluid density, and

is the fluid density, and  the pressure. If we now make the assumption that

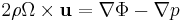

the pressure. If we now make the assumption that  is scalar potential and the advective term may be neglected (reasonable if the Rossby number is much less than unity) and that the flow is incompressible (density is constant) then the equations become:

is scalar potential and the advective term may be neglected (reasonable if the Rossby number is much less than unity) and that the flow is incompressible (density is constant) then the equations become:

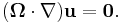

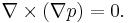

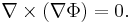

where  the angular velocity vector. If the curl of this equation is taken, the result is the Taylor–Proudman theorem:

the angular velocity vector. If the curl of this equation is taken, the result is the Taylor–Proudman theorem:

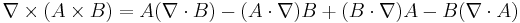

To derive this, one needs the vector identities

and

and

(because curl of gradient is always equal zero) Note that  is also needed (angular velocity is divergence-free).

is also needed (angular velocity is divergence-free).

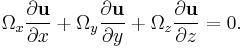

The vector form of the Taylor–Proudman theorem is perhaps better understood by expanding the dot product:

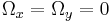

Now choose coordinates in which  and then the equations reduce to

and then the equations reduce to

if  . Note that the implication is that all three components of the velocity vector are uniform along any line parallel to the z-axis.

. Note that the implication is that all three components of the velocity vector are uniform along any line parallel to the z-axis.

Taylor Column

The Taylor column is an imaginary cylinder projected above and below a real cylinder that has been placed parallel to the rotation axis (anywhere in the flow, not necessarily in the center). The flow will curve around the imaginary cylinders just like the real due to the Taylor-Proudman theorem, which states that the flow in a rotating, homogenous, inviscid fluid are 2-dimensional in the plane orthogonal to the rotation axis and thus there is no variation in the flow along the  axis, often taken to be the

axis, often taken to be the  axis.

axis.

The Taylor column is a simplified, experimentally oberved effect of what transpires in the Earth's atmospheres and oceans.

References

- ^ The Taylor-Proudman theorem was first derived by Sydney Samuel Hough (1870-1923), a mathematician at Cambridge University. See: Hough, S.S. (January 1, 1897). "On the application of harmonic analysis to the dynamical theory of the tides. Part I. On Laplace’s “oscillations of the first species,” and on the dynamics of ocean currents". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 189: 201–257. Bibcode 1897RSPTA.189..201H. doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0009.

- ^ Taylor, G.I. (March 1, 1917). "Motion of solids in fluids when the flow is not irrotational". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 93: 92–113. Bibcode 1917RSPSA..93...99T. doi:10.1098/rspa.1917.0007.

- ^ Proudman, J. (July 1, 1916). "On the motion of solids in a liquid possessing vorticity". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 92: 408–424. Bibcode 1916RSPSA..92..408P. doi:10.1098/rspa.1916.0026.